The Ceiba; Sacred tree of the Maya

For Maya communities, the ya’ax’che is a sacred tree holding up the sky with its branches and reaching the underworld with its roots.

Perhaps the most magical aspect of ancient cosmogonies is that they see divine qualities in nature and its many facets, in animals and plants. It’s an intimate connection our ancestors kept with their environments. Not only did they observe and learn from nature, but they deeply revered it. In our own time, recovering such a relationship may be essential.

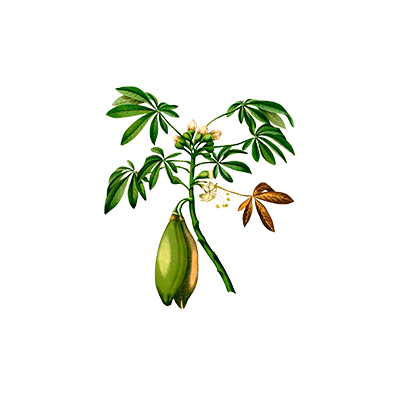

Ceiba, Mexican tree

A few contemporary communities keep such a sacred correspondence active. Among the Maya, the cult of the ceiba (or ya’ax’che) is still practiced. The ceiba is a special tree which appears in several Mexican cultures. In some southern regions of the country (such as in Oaxaca and Morelos), it’s known as “ceibo” or “pochote” (from the Nahuatl pochotl). The bark is used to make handicrafts.

A beautiful tree, it can grow up to 70 meters tall and reaches a diameter up to three meters. Its generous canopy grows forming various “floors” of branches and leaves. The tree’s flowers of fleshy petals give off a peculiar perfume. It’s also well-known for its magnificent roots which fit into the ground capriciously, seeming to exhibit the very power of its anchorage.

In many communities, the ceiba is appreciated for its medicinal qualities. Traditionally bark, leaves, and stems are used to heal wounds and to treat acne. It’s used to relieve symptoms of rheumatism, intestinal diseases, inflammation, toothache, burns, and rashes. But above all, it’s a sacred tree

Legends and Rituals of the Ceiba

Perhaps it was the tree’s peculiar form that suggested to the Maya that the ceiba is a divine tree. Even contemporary Maya groups consider it “the tree of life.” It’s thought that the branches form the sky and, with its roots, weave the underworld, connecting on three cosmogonic levels. The trunk, maintaining the earthly plane, is also a conduit for communicating with the other levels.

As Alfredo López Austin wrote:

The tree is the quintessential figure to understand, with its veins of sap, the ways the divine flows from and communicates with both heaven and the world of the dead , and unites the cosmos while bringing movement to the world of creatures […].

According to the anthropologist, Alfred M. Tozzer (cited by researcher, Elsa Hernández Pons), to the Maya, there are 13 celestial planes, arranged one on top of another. These are visible as the different levels of the tree’s canopy. The planes have, in their centers, a hole through which the trunk passes and through which the souls of the deceased climb. They’ll reach the level corresponding to the virtue they achieved in life. Pons, an archaeologist, has pointed out that for some groups, the ceiba is considered the “abode of the gods.” It’s associated with the cross, “[…] clearly expressed in the crosses placed at the bases of some trees, especially those growing at a crossroads or highway exit.”

The shadow of the ceiba is also a ritual space. At the foot of the tree offerings are deposited and respect is offered in the tree’s shade. Ceibas are also planted in plazas and, during certain Yucatan religious festivals, the ceibas are ceremonially crowned “queens” of the celebration.

Adopting the Cult of Ceiba

The cult of ceiba is admirable, corresponding more generally with other tree cults. As an everyday natural object —sometimes insignificant— we depend on it in very profound ways. Trees release oxygen. They absorb CO2. They unknowingly combat climate change. They retain water. They’re a refuge for all kinds of animals and they refresh their places with shade. But if these are not enough reasons to consider them sacred, it’s worth remembering, too, that with their branches they hold up the sky.