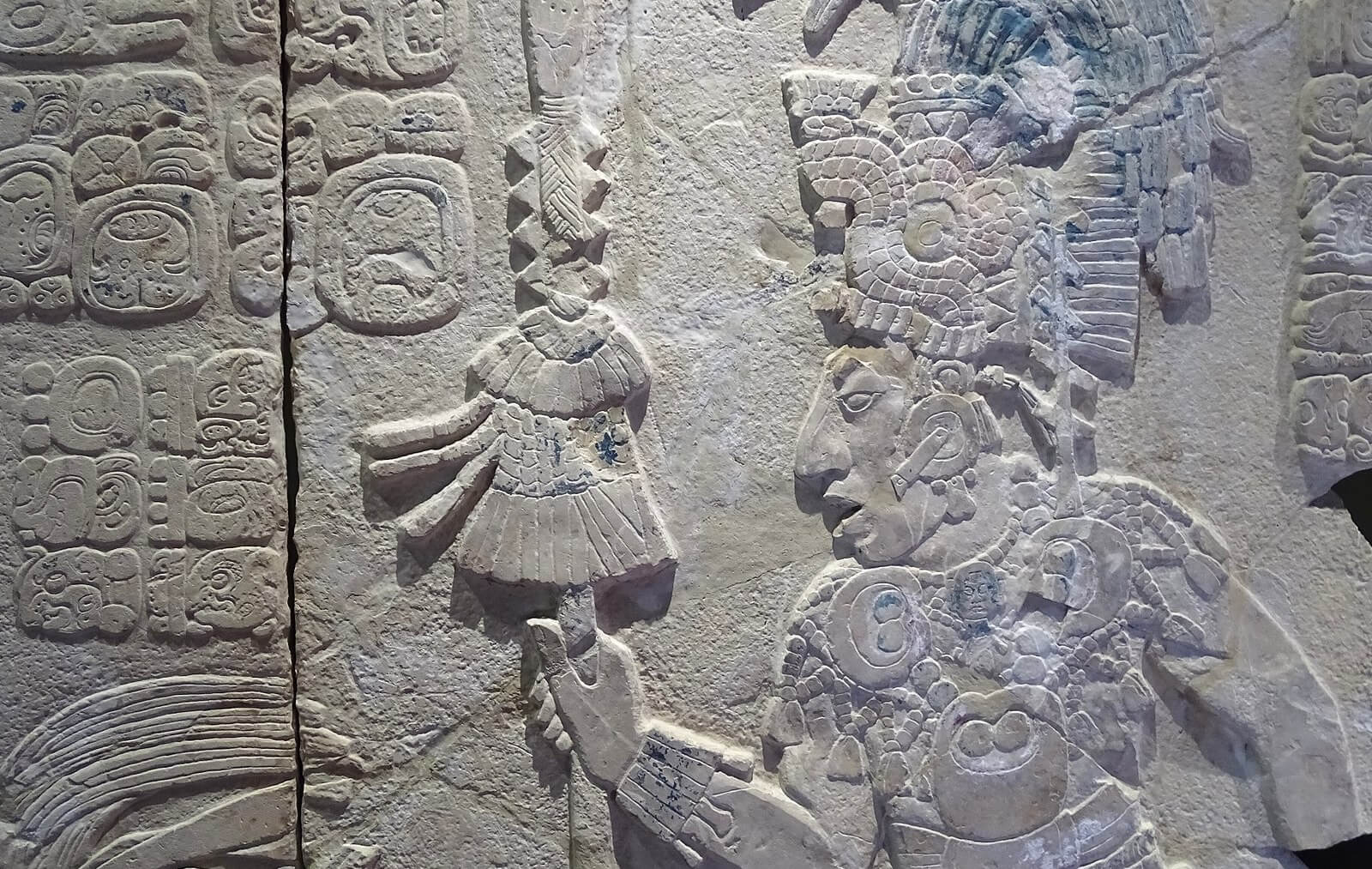

Contemporary Maya Thought on Space, Time, and Humanity

The Maya philosophy of today is as captivating as it was in the ancient world.

Maya peoples, despite the passage of time, have held onto the philosophical teachings of their ancestors. Of course, such knowledge has been transformed. The life experiences of every one of them have imprinted new information onto a collective cosmogony. But the Maya stand out among other cultures native to their countries. Having assimilated the experience of conquest, they’ve maintained their own languages, traditions, and worldviews.

Looking at this symbolic, conceptual heritage is relevant today, and many contemporary initiatives are making it possible. Among these is the Baktún Initiative. The project’s aim is to make the knowledge of Maya communities visible, to honor them, and to learn from them in the present.

In the contemporary Maya cosmogony, we can look for concepts and definitions that will potentially make our own existences richer. There are unexpected explanations for our origins, our purposes, and our possibilities for relating physically and spiritually with the environment. We’ll explore a little Maya philosophy on space, time, and the notion of humanity below.

Space

Among the Maya—as with other indigenous communities—divisions between nature, culture, subjectivity, and spirituality are not as clear as they are for other western cultures. As researcher Ariadna Estrada Ochoa explains it, these categories are contextual. That’s to say, “obey specific circumstances” and things pass between all of them, constantly. Space is not something outside oneself: it’s the terrain where all these forces unfold.

Physical space and the things within it merge with institutions, policies, and beliefs that govern them. Thus, explains Estrada Ochoa, the space between the Maya is the territory, “a notion that’s intimately associated with a community’s identity, its internal political and social relations, and with the outside.” Space as territory has an indissoluble relationship with the people within it, as both entities take advantage of the presence of the other to survive.

In such a way, the researcher writes, “that space itself is conceived as an entity, an otherness with which it interacts and dialogues.” Space, for the Maya, has its own interests and you need to learn to dialogue with them.

Time

David S. Stuart, a prominent Maya researcher, writes in his book The Order of Days: “Maya time, it would be fair to say, is the deepest in all humankind.” Stuart is referring here to the complex processes of recording (and the invention) of the time which articulated ancient Maya cultures. Stuart argues that Maya time lasts “much” longer than our own, because the origin of their cosmos occurs long before our own. But what really broadens the chronological dimension of the Maya is that they record multiple times.

Maya time (or kin) is cyclical. As researcher Pedro Bracamonte y Sosa put it, the prophecies and predictions are “nodal elements of Maya culture.” Maya communities have historically believed that the present needs to be recorded and analyzed to prevent the future. In such a way, the past dictates what the future will look like. Something that happens, will happen again, when its time comes again.

In the present, such an idea isn’t based on superstition, but on the empirical experience of the repetition of natural and cosmological cycles. Maya time, Bracamonte y Sosa writes, unfolds as an analogy of itself. As Stuart explains, time isn’t just one: every cycle is a time, the prophecies, or omens of which can correlate with other times.

Thus, more than a cycle, Maya time is a spiral. But it’s not immovable because constant foresight allows one to modify the direction of time, reacting to omens with rituals and ceremonies.

The Maya are not the only culture to pay attention to patterns and omens. Some other cultures from the West have also charted the path of its history based on speculation. But recording times, observing our own cycles and what surrounds us, and learning to interpret them through our own experiences, could still be a profound practice of self-awareness.

Humanity

“The Maya understand themselves with the environment,” writes researcher José O. Alejos García. While in other cultures we identify only with what we’re like, and we’re certain of what we are begins and ends, the Maya think that “a part of being is outside of itself.” It thus merges with its other. Being human, for the Maya, is no different from being natural, being an animal, or being a spirit.

Less focused on the definition of humanity, Maya philosophy thinks of the being of things. At the same time, identity is relative; one is not one, but can be transfigured into another. One may be inhabited by another or inhabit another, depending on the circumstances. Being is a set of links. Thus, the experience of being is relational, not individual nor self-referential.