The geodesic dome: geometry at humanity’s service

Buckminster Fuller, architect and thinker, claimed the world could be designed to satisfy all of humanity. That dream resonates to this day.

Richard Buckminster “Bucky” Fuller, suggested on multiple occasions that humankind “has a function in the universe, in being its conscious, anti-entropic part.” Hugh Kenner described Fuller’s thought thus in 1972. It’s in our nature to design the world, to plot paths between seemingly disconnected points, and when those connections are discovered, to make up meanings for them.

It’s not uncommon for geometry to be the language chosen by the architect to speak of functionality, ecological awareness, and parallels between social processes and those of the Earth, and to design with a humanist vision. In geometrics—or more precisely, in the geodesic—Fuller found a way to articulate cities, homes, cars, and roads that served each of their users and inhabitants in a balanced way.

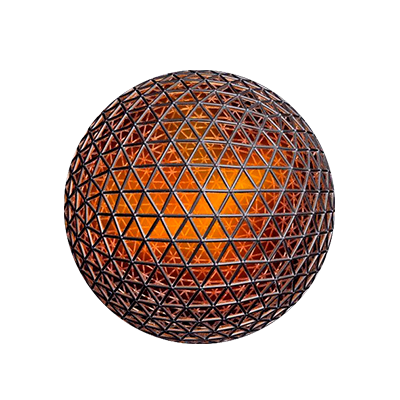

Fuller’s best-known design is a geodesic dome, a spherical or semi-spherical structure composed of triangular or polygonal facets. It was manufactured, in principle, for the purpose of serving as an accessible home. Its efficiency can be seen in multiple aspects. Beyond the design which allows tension to be distributed throughout the structure (instead of at a few base points), it requires little physical material to be built, and encloses larger volumes with a smaller surface area.

At the same time, erecting such a design and making a home of it doesn’t have to be expensive, either. (One of Fuller’s domes was made of cardboard.) Its energy efficient isn’t limited to just the structure. A geodesic dome maintains stable temperatures inside, and its concave interior allows for a free passage of air.

When Fuller imagined geodesic domes, after the many crises of the 1920s and the sociopolitical consequences of World War II, his country—the United States—was reincorporating itself. While the buoyant 1950s meant industrialization, modernization, and the growth of America’s big cities, many people had been left behind. To Fuller, the situation had not gone unnoticed.

A need to design to the satisfaction of the whole of humanity propelled the dome into the fields of efficiency and sustainability. Although these concepts hadn’t yet achieved the prominence they enjoy today, Fuller was sensitive to the ecological aspects of architecture. In his opinion, great architects of the time freely spent new materials to build inefficient buildings. He was already preaching in favor of recycling. And Fuller believed that everything necessary for human subsistence already existed; it just had to be used in the right way.

For many, his ideas like his designs were the delusions of an eccentric. The geodesic dome had its star moments. One was a 76.2-meter diameter dome for the 1967 World’s Fair in Montreal, Canada. But few postwar Americans imagined themselves living in a house with curved walls, scarce privacy, and where sound travels evenly.

Such details revalidate Fuller’s approach though. Even today we might ask ourselves why urban and domestic designs tend to be square? Little of our furniture would have a place inside a geodesic dome if for nothing else then for the simple fact of our furniture’s straight lines. And we never question straight lines. This is despite the fact that the planet draws us again and again towards the curved and the circular, in the processes of nature, always cyclical and in the shape of the Earth, spherical.

The geometric of the dome—its mathematical essence—seems to suggest the inimitability of nature and its organic principles. Fuller marveled at the efficiency with which some natural objects—snowflakes and flowers—develop according to geodesic principles.

The spherical planet was Fuller’s ultimate source of inspiration. Fuller imagined a geodesic space from which one might admire the entire world and connect all if its points, as if one were living in the center of the Earth. This would fulfill another of his missions in life: to not interrupt the flow of nature’s energy with our own patterns.

Questioning lines and preferring spheres that connect points is one of R. Buckminster Fuller’s main legacies. The principle of the geodesic dome is “to make the world work for 100 percent of humanity in the shortest possible time through spontaneous cooperation, without ecological offense or the disadvantage of anyone.”

It sounds terribly ambitious, maybe even unhinged, but as artist Jonathon Keats said in Wired magazine: “Failing at something is much more productive than succeeding with a more limited set of restrictions.” Fuller himself said: “If the success or end of this planet and human beings depends on how I am and what I do… what would it be like? What would I do?” His voice resounds today.