The Glass Key (mirror travelers) at Hacienda Ochil

Artist Charles Stankievech interweaves the sounds of nature to enable a dialogue between the environment and the audience.

Daniela Pérez & Charles Stankievech

What we commonly recognize as the sound of water, comprises only a minor fragment of the vast sonorous language that water speaks. Only by paying close attention can we listen acutely enough to identify what could seem as imperceptible to our ears at first.

In such regard, the artist Charles Stankievech has invested a considerable amount of time researching how to gain access—both physical and technological—to sites that allow entry points of connection with very unique sounds, including those emitted by the rising sun, a thunder, or shrimp in the depths of the ocean. The vast field recordings archive that Stankievech has compiled is shared throughout his work in different forms and ways.

Only a few weeks ago (May 2021), he immersed himself—and, of course, those fortunate travelers and audiences that were present at Hacienda Ochil in the municipality of Abalá in Yucatán—, to testify and participate in a real-time live mix of audio design that incorporated raw, harmonious, and melodious sounds. Beat after beat, the music drew attentive listeners deeper into the juxtaposition of experiences pertaining sounds from solar radiation, lightning strikes, the ocean and its inhabitants, as well as water recorded with hydro-microphones from cenotes throughout the Yucatán Peninsula.

Setting a path in a deliberate attempt to establish closer connections with an element such as water, TAE Foundation was fortunate to collaborate openly in joining forces and interests with Charles Stankievech and the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin, who originally enabled the overall commission of a similar work presented as part of an online exhibition, The Last Museum, which among other things, suggests that the concept of site-specific is reimagined according to digital times.

As a temporary sound installation for a live audience at Ochil, upon arrival to the hacienda, visitors were invited to observe and contribute to an offering of fruits, seeds and plants that changes according to the passing season. After wandering through the historically and culturally charged site, and once closer to the enveloping sound from The Glass Key (mirror travelers), one was free to move around and perceive the dramatic fluctuation of sound depending on the selected spot. The rear of the stage at the mouth of the cavernous cenote, for instance, allowed a resonant amplification of the overall installation.

The contemplative scenario for the performance in the open air—connecting both sonically and architecturally, the sky and the underworld cenote at Ochil—, became a forum for stimuli where local natural sounds generated a dialogue with Stankievech’s mix of previous recordings. The artist put into play a profound exercise on intuitive focus and endurance as a performative element that energized the space.

Such was the intensity accumulated in the concave amphitheater designed by James Turrell, that 2.5 hours into the layered live-sound installation titled La llave de cristal (viajeros espejo) [The Glass Key (mirror travelers)], 2021, an unpredicted downpour—the first of the season—invaded the site. The natural conditions enabled a tangible connection with the rain falling heavily from the sky on all of those present at the site. While unplanned, we shifted from an immersive listening to the water cycle via the representation of sound recordings, to being actually submerged under rain-showers, completing a full connection with nature on its own terms.

A Dialogue With the Artist

Today, as we calmly await a sound recording that the artist is putting together as a result of the sound installation presented at Ochil to be shared in our platforms thinking of asynchronous audiences too, it seems pertinent to expand the dialogue with Charles Stankievech after the event.

What did you hear in the waters in the Yucatán Peninsula?

The waters of Yucatán host the incredible extremes of listening. For example, [the biosphere reserve of] Sian Ka’an (with its lagoon estuary mixing salt water and fresh water) hosts an incredible amount of biodiversity, but the dark and more hermetic cenotes hold an intimidating silence-one we have projected our deepest fears into: the abyss of the underworld.

In the discipline of field recordings (along the lineage of R. Murray Schafer, the founder of the World Soundscape Project and my grad school mentor) a diverse biosphere is also one that is diverse in its sounds. Sadly, we’ve been seeing for the most part across the globe from the West Coast of Canada to the Amazon Rainforest a significant drop in wildlife sounds, which indexically signifies a loss of biodiversity. Since I’m only witnessing a singular time slice of recordings in the Yucatán Peninsula, I can’t make these comparisons that take decades of sampling, so my observations are more about the inherent contrast of the radically different ecosystems at play in such a complex territory: from sea to cenote.

You have mentioned that New Zealand granted a river the status of personhood. What ritualistic social act would you suggest we collaborate as a society to bring forward in terms of care for our water(s)? How does site-specific art recognize and understand nature as subject with rights instead of an object of abuse?

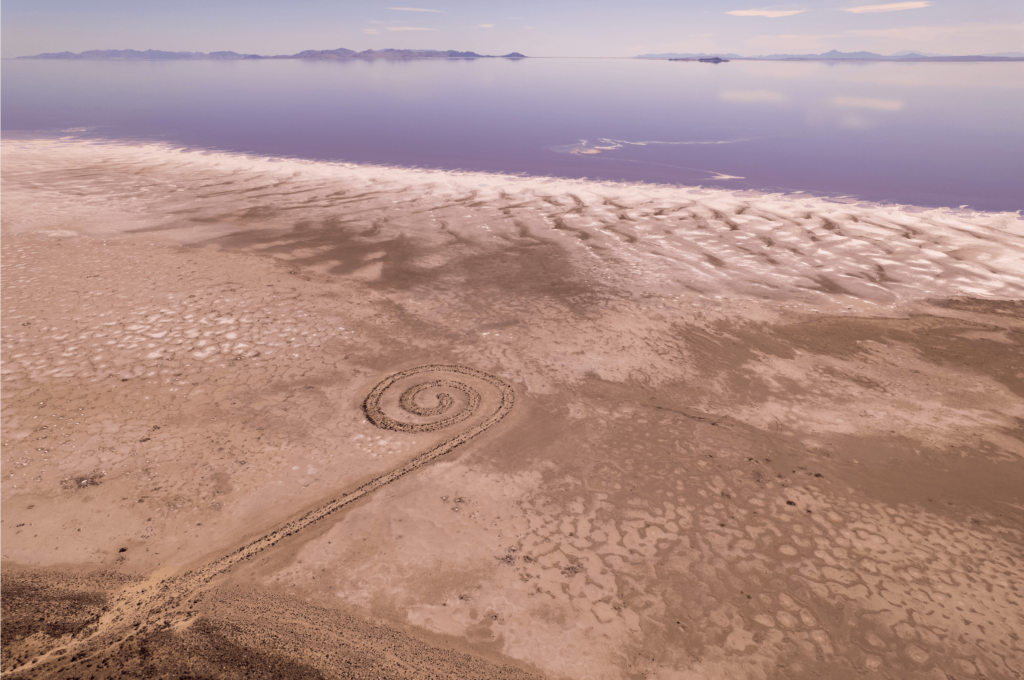

This is a complex question and one historically contingent. Part of the research in the Yucatán Peninsula was tracing the American land artist Robert Smithson’s travels there in 1969. After the project in Yucatán, Ala Roushan and I continued tracing his and Nancy Holt’s travels to his Spiral Jetty, constructed in 1970: from Yucatán to Utah (we also stopped at Michael Heizer’s Double Negative and Holt’s Sun Tunnels). This era—the birth of site-specific art—wasn’t that sensitive to nature as a subject; in fact, they were radical incisions into the landscape, ones that could only be done in industrial landscapes like the Salt Lake or a remote desert.

Such work continued the Manifest Destiny of American ideology as fetishized by the German artworld (which brought this work to international acclaim): Lawrence Weiner blew up the land to make craters in California, Michael Heizer dug trenches in Nevada, Walter De Maria drilled through earth, Robert Smithson extended a road out into a lake. The works as I list them sound a lot like the infrastructural acts of, say, building the Hoover Dam. None of these works cared for the land or its inhabitants, but only for the grand gestures of frontier exploration à la avant garde art.

A little-known anecdote, but Smithson’s failed attempt to make an Island of Broken Glass off the coast of Vancouver was due to local environmental concerns and the politics of the Vietnam War. He shifted to the much less regulated landscape of the Utah Desert as a result. Contemporary site-specific work is more instep, as is the rest of culture at large, with environmental concerns and critiques of the anthropocentric.

The legal battle you’ve mentioned in NZ took an incredibly long time (140 years) and is part of interesting work respecting indigenous treaties and diverse cosmologies/ontologies. For the most part (at least in the European derived territories), our legal frameworks support an “instrumentalization” of nature based on Judeo-Christian values, which on today’s scale of global industrialization needs to be rethought. However, a romantic return to indigenous cosmologies is also not a solution to the dilemma of the current population of the planet (the 1970s ‘back to the land’ movement already articulated this failure).

This is where art provides a bridge, testing and challenging accepted practices both of the past and the present. Sometimes the easiest thing art, or ‘ritualistic social acts’ as you say, can do is create open spaces and a slowing down of our production. Listening is an important part of this process. My Distant Early Warning Project (2009) attempted to create a remote techno listening station for melting ice in the Arctic. The sound installation here in Yucatán was a ritual of us listening together. The composition used the strategy of a very long slow fade in and out, in order to mix with the local soundscape, and this way we start to train ourselves to not stop listening to the world around us even when the artwork ceases.

You recently referenced Robert Smithson’s If an artist could see the world through the eyes of a caterpillar he might be able to make some fascinating art… What do you imagine that the visibility of your sound recordings can convey, in terms of expanding possible symbiotic living as part of nature?

One of my strategies in field recordings is to broaden human perception. I translate the frequencies of solar radiation into sound vibrations (without scaling them). I use hydrophones to record the depths of the seas. I scale ultrasound into the human range of hearing. All these attempts to listen beyond our body’s physical perceptions expands our appreciation of the world’s dynamic range of interactions. It’s very anthropocentric to understand the world according to our natural body’s limits, but it is even more so from a so-called “objective” scientific mapping. Our scientific frameworks are human constructs even though they use numbers and data (I’ve written a bit about infrared light in the same way here).

By creating immersive and subjective impressions of the environment that include transcoding, translation and scaling, we can start to imagine other subjective positions. Of course, we can never know “what it is like to be a bat”, but our failure in trying enriches our appreciation and increases our understanding of the complexity of our world. Art has the freedom to explore these failures, and one hopes—like the genetic mutations as a result of transcoding errors—we evolve and adapt in relation to our ecosystem.

Water is fluid, is one and many—its collective—, its porous… it links moments and places to each other, how does that connected territory reappear throughout your own artistic ideas? Perhaps this allows us to further expand on the impact that melting glaciers from the Arctic has not only in Toronto as the largest freshwater reserve, but also all the way into the profound caves of cenotes in Yucatán (as a result of the meteorite that impacted here and shaped the local landscape).

What I find interesting about the fluidity of water is its timescale. On the one hand it can come crashing down in a flood or occupy our daily checking of the weather. On the other hand, it is where life first evolved on this planet and it shapes continents over epochs. Yes, as volume, as a flow, water connects the entire globe, but as a medium of time it also connects us across pre-history and into the future. In this way it is always lurking and flowing through my work. Most recently, I curated The Drowned World, a program of sound and video art for the inaugural Toronto Biennial (you can download the catalogue here). This project not only connected the melting of glaciers to the rising sea levels in the South Pacific, it also connected prehistoric cave art in dripping caverns with the flooding of the Seed Vault in a high tech bio-archive. Water allows us to move seamlessly through such vast areas and times as a connective tissue.

The other probably longest running material in my work are meteorites. Meteorites function as similar markers and agents within a deep time scale and of course at acute moments of atmospheric entry. The Yucatán Peninsula feels like an old landscape with its well-preserved ruins and the cenotes that feel like ancient portals—and this is true on a human timescale, but geologically speaking, it’s a very young landscape. Where I shot a related project in the Canadian Rockies (The Last Museum as mentioned above), the landscape is tectonic and much older. The Peninsula is much younger and its fracture of limestone by a meteorite “only” happened 65 million years ago.

This flow of water and the impact of a meteorite that happened spectacularly in the Yucatán also brings these two interests of mine together. I’m currently working on a long-term project that started in 2012 in Marfa, Texas, when I was doing the residency there and created a work called The Desert Turned to Glass—a hovering meteorite suspended above the ground moments before it pulverizes the sand turning it into glass. Locally, in Yucatán, the Chicxulub meteorite fractured the crust and created a labyrinth of caverns filled with water, which are relatively speaking devoid of vertebrae life but full of microscopic life. Culturally, they function as portals to the underworld.

Inversely, I’ve been fascinated with the theory of panspermia—that our planet was seeded with microscopic life as delivered via a meteorite. The meteorite becomes not a portal but a vehicle from other worlds. In 2000, we recovered the first meteorite in a frozen state. It crashed into a frozen lake on the border of the Yukon Territory and British Columbia (Canada) and was immediately recovered by someone ice fishing, so we have the possibility to study it for ice and possible life frozen in ice crystals. Water is necessary for life to evolve, and as it turns out is probably necessary to transport interplanetary life.

Aligned Stars

During such times, it is of utmost importance to lay out the fundamental need for organizations and individuals to defend and find different forms of activating change in order to act, collectively, in far more radical and committed ways. So if we must positively exploit each other’s capacities and vantage points to allow further audiences to encounter approaches that proclaim, in different levels, an urge to establish new and diverse forms of coming close to nature as part of society, we shall confirm our paths towards gatherings that site-specific art can proclaim, indeed powerful in current times.