The cow in art, mythology, and culture

Symbolic and replete with timeless inspiration, an animal appears in all human cultures and takes countless forms.

And this prayer of the singer,

continually expanding,

materialized in a cow that had been there before,

the beginning of this world.

—Rig Veda, 10:31

Since time immemorial, the close relationship between people and animals has produced such a deep bond that they’ve been an essential part of our beliefs, mythologies, and legends. Our fantastic, ontological explanation of the world is populated with animals, and many of our deities are embodied by them. From insects to ferocious beasts, all kinds of creatures have been included in our mythological mind. One of these beings holds a special place, the cow.

Cattle were among the first animals domesticated by humankind. It took place some 10,000 years ago. In many human cultures, cows symbolize fertility, generosity, motherhood, the origins of life, and they’re related to serenity. Cows, and their male counterparts, are recurring presences within mythologies and ancient religions. The cow is an animal, yes, but it’s also a powerful symbol, myth, and metaphor.

The mystical, mythological, symbolic character attributed to cattle has been a starting point and a central theme in artistic works over the entire course of history. They illustrate and contextualize humanity’s most varied beliefs and views. The cow is a protagonist and companion in the visual narrative of our existence, appearing inevitably at every moment of art history, from cave paintings, to practices in our own contemporary age.

For all these reasons, cows have figured, in multiple forms and ways, in the arts as the bearers of manifold and fascinating meanings.

The Dancing Cow

Hathor was a goddess of love, joy, and dancing in Egyptian mythology. Originally a representation of the Milky Way, she was literally, milk flowing from the udders of a celestial cow. It’s due to her that we call our own galaxy as we do. Later, she was depicted as a woman with cow horns, and as a cow between whose horns is a solar disc. In ancient Egypt, cattle were symbols of fertility. It was also believed that the fluctuating level of the Nile River depended on them.

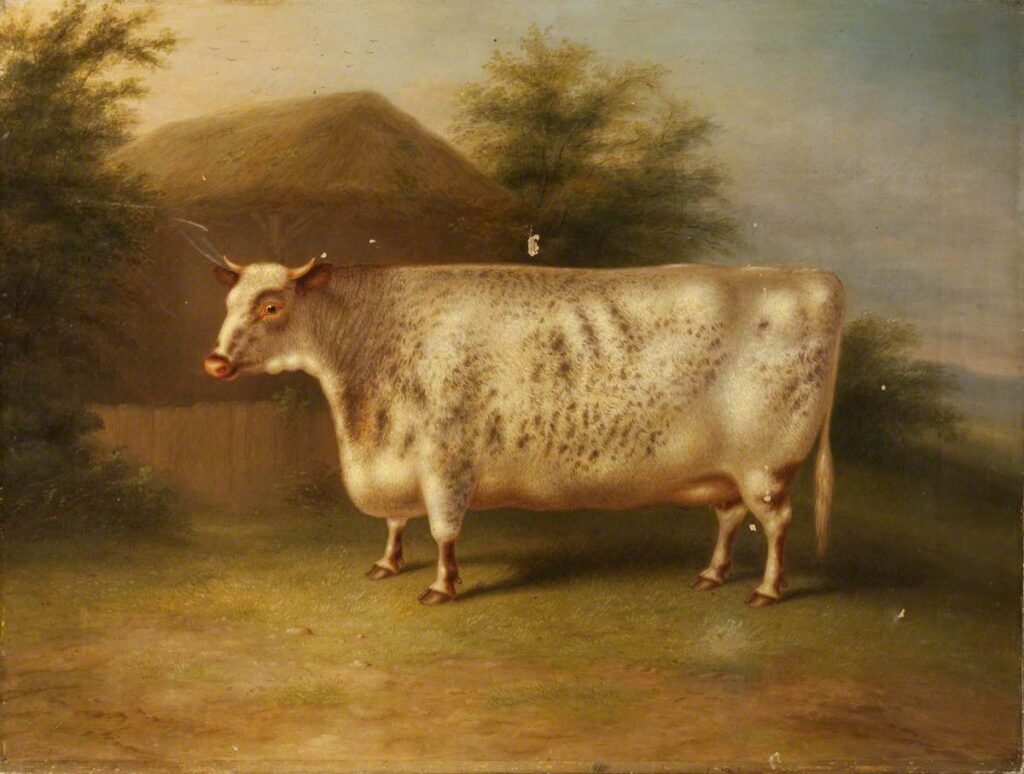

The Rectangular Cow

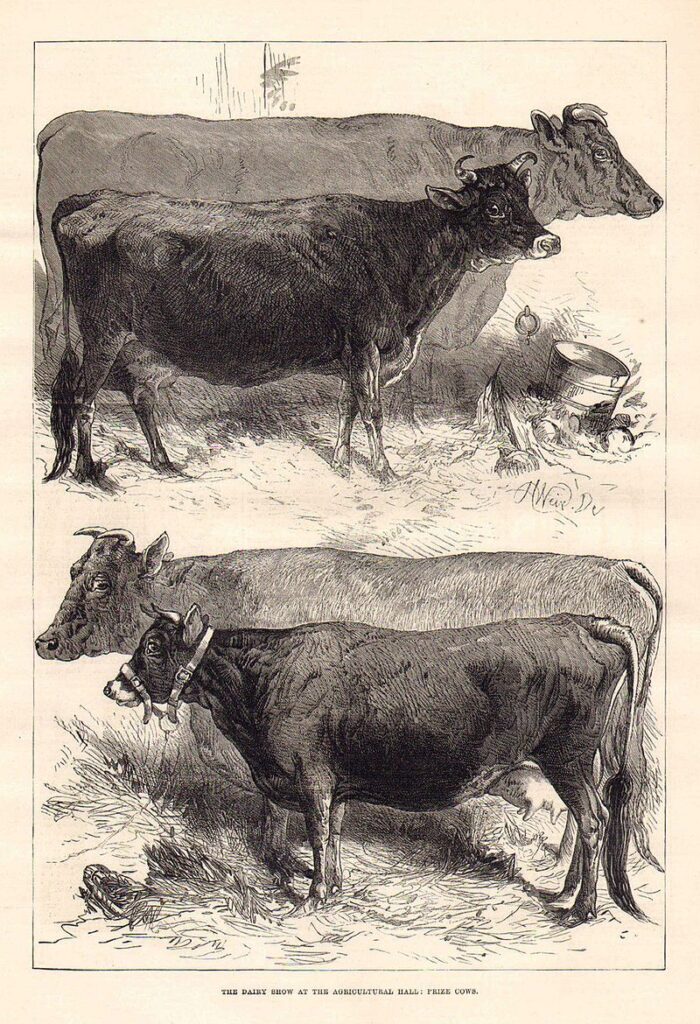

In 18th-century England, paintings of “rectangular cows” became commonplace. They were cattle caricatured within realistic scenes, with heads, legs, and tails of a noticeably lower proportion in relation to the rest of the body. That was exaggerated, muscular, and bulky. The mode of representation was connected directly to the Agricultural Revolution. It was a time of remarkable development, and rural production, and one in which cows played a leading role. Technological advances allowed, for the first time, for selective, specific breeding in livestock. A common practice among powerful breeders was to commission local artists to produce pictorial portraits of the animals—a proud record of their successful rearing and a symbol of the breed’s power.

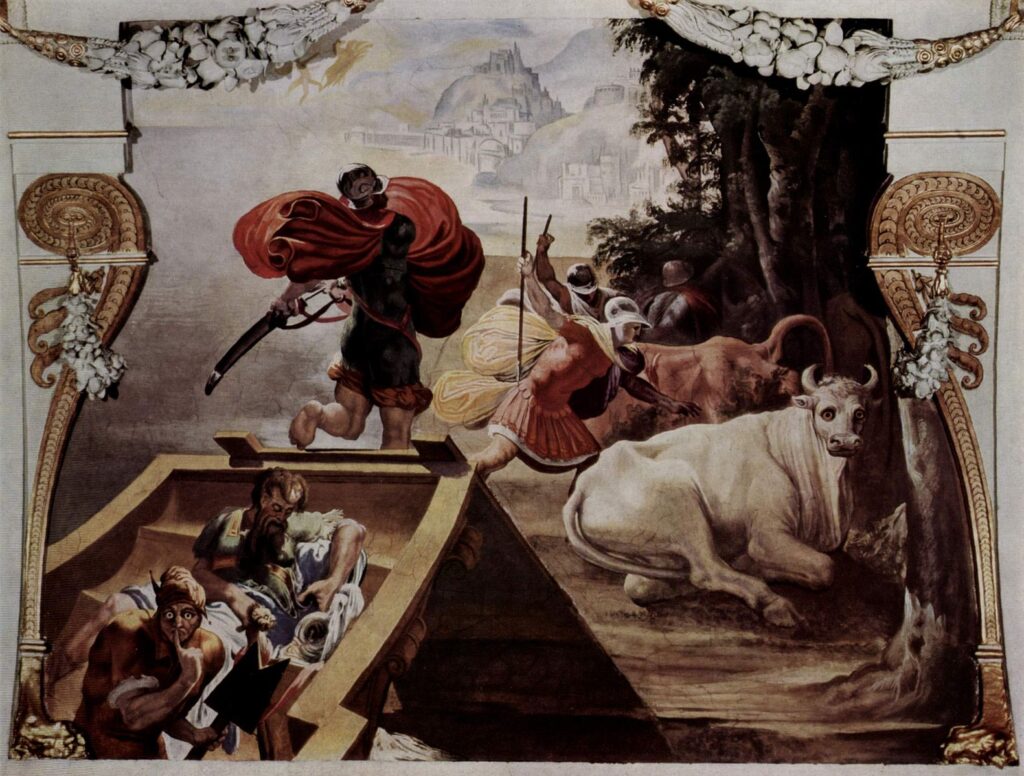

Cows of the Sun

In literature, cattle have been recurrent and fulfilling. Varying by author and context, cows perform multiple narrative functions. In The Odyssey, Homer describes Ulysses’ fellow travelers’ decision to sacrifice and eat the forbidden cows of Helios, the god of the sun. In response to the disrespect, Zeus casts a lightning bolt which destroyed the ship killing everyone on board except Ulysses.

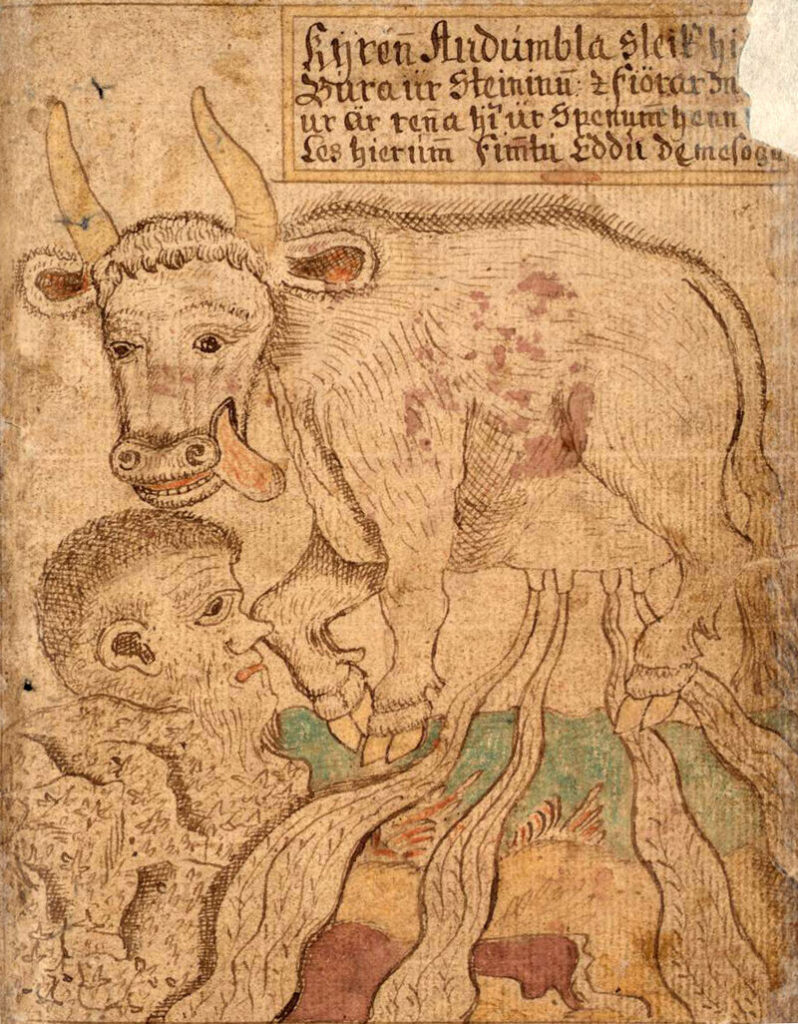

The Great Cosmic Cow

In Norse mythology, the first living being, the one from which all the rest emerge, was a giant named Ymir. A colossal being, he fed on the milk he drank from another primal being: Aðumbala, the great cosmic cow—a bovine that arose from the ice of Niflheim (a kingdom of darkness and obscurity and a kingdom of dragons). The cow fed on salty pieces of frost melted by the Muspelheim (a kingdom of fire and home to giants). In licking the ice, Aðumbala revealed the figure of a man, and thanks to the cow’s tongue, eventually released him. This man was Buri, the first god of Norse mythology.

A Cow Called Serpentina

A series of unfortunate events happened to a rural Mexican family. The story begins with La Serpentina, a cow “with one white ear, and another colored, and very beautiful eyes.” She disappears when dragged down the river. The event, as though it were a bad omen, expresses the symbolism of the animals in Mexico. The cow here functions as a common thread running through a moving tale entitled, “We’re just very poor,” collected in Juan Rulfo’s The Burning Plain.

The World of Cows

In India since ancient times, cows have been considered sacred animals. Krishna, the eighth incarnation of the god Vishnu, is said to have grown up within a herd of cows. This made him the guardian and protector of cows. (It’s also why, according to a vision, the world is full of them.) Krishna lived in a land of plenty, of wealth, and natural beauty. In Sanskrit, the place was called Goloka, which means “world of cows.” The unique relationship with the figure of the cow has remained, among Indians, practically intact even to this day. Much of the population of India considers them a sacred animal and will not kill or eat them. On the other hand, in the oldest Indian sacred text, the Rig-Veda, the presence of cattle constantly reappears within the Sanskrit hymns dedicated to the gods. In these texts they refer to the cow as aghnya. An approximate translation is “that which cannot be sacrificed.”

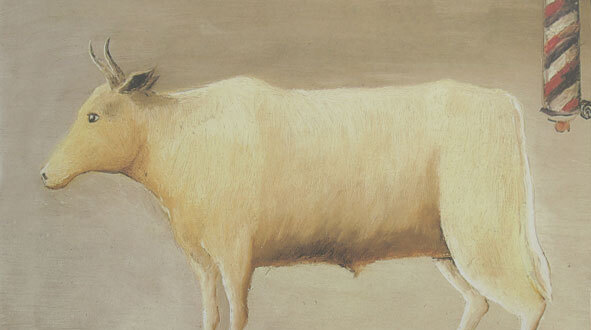

La Vaca Independiente

A key character in the history of Mexican graphics was Abel Quezada. A multifaceted artist, through his caricatures, paintings, and texts, he portrayed and criticized the complex and fascinating reality of Mexico. Quezada began as a self-taught painter at an advanced age. His pictorial work, mainly focused on portraiture and landscape, is characterized by a simplicity of stroke and a dazzling use of color. A little-known but unique work by the Monterrey-based artist was La Vaca Independiente, i.e., The Independent Cow (1979). In oil on a very large canvas, the painting depicts a cow in profile. In light shades of brown, yellow, and white, the cow stands on a dark floor before a neutral background. The cow looks to the viewer’s left, contemplative, tender, surprised, and solitary. At the far right of the composition is an artifact, a blue and red rotating cylinder, such as those once used to identify barbershops. The painting holds an enigmatic beauty, almost absurd, and seemingly naïve. It invites one to decipher the messages traced into it. Quezada’s work, and particularly this work of art, served as inspiration and as a trigger for the cultural dissemination project, La Vaca Independiente.